Consultation for RLE/CLE

This is the basic information I provide in my consultations for a Refractive Lens Exchange (RLE) also called Clear Lens Extraction (CLE) or cataract procedure with the implantation of a modern multifocal lens. It is important that you read the below as if you were preparing for an examination so that you retain critical information and generate thoughtful questions for our consultation.

Having an elective surgery with a multifocal lens is a very serious decision and would affect your vision for the rest of your life. Similar to sitting your driving test (and you need to demonstrate basic understanding of traffic laws) you need to demonstrate to me your understanding of the risks you are taking and confirm your awareness and acceptance of the side-effects of multifocal lenses because the outcome cannot be demonstrated prior to the surgery and there are no guarantees or promises that can be given.

Most of the time patients worry and say ‘I hope it goes well and it is successful’. The success of this surgery depends more on your expectations rather than the occurrence or not of any complications. This is 100% true in that I will remove your natural lens and replace it with an artificial one. The important question is what vision will your brain perceive through this new multifocal lens and whether this matches or approximates your expectations. Being a surgery nobody can promise or guarantee anything to you.

As this is an elective surgery you can continue using or try new spectacles and contact lenses of either single or multifocal type, you can even try a monovision i.e. one eye for distance and the other for near. The choice of a multifocal Intraocular lens (IOL) is currently the most popular solution for spectacle independence, however, it is a compromise and may not be indicated for perfectionists.

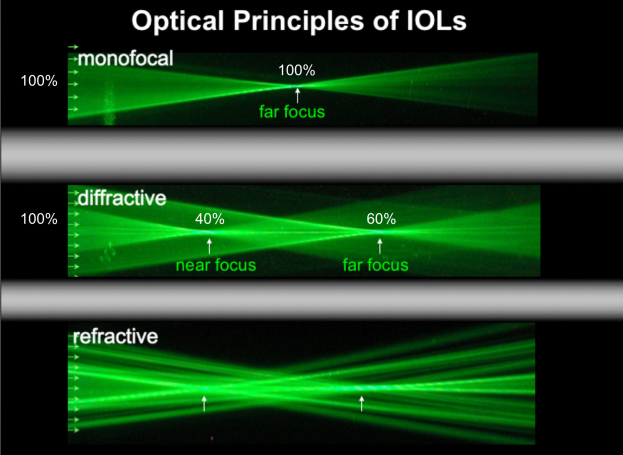

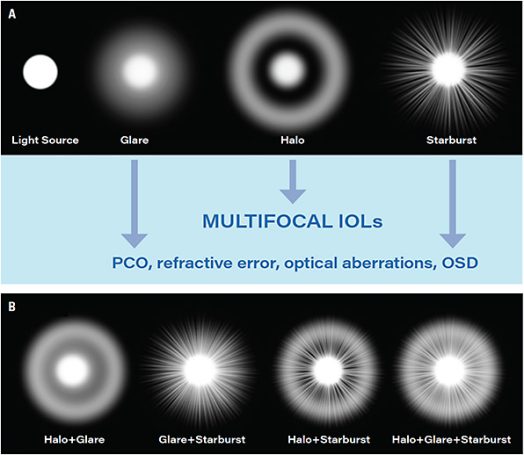

All through your life, your vision was monofocal and through a process called accommodation (until the age of 40-45) you were able to change the shape of the natural lens inside your eye thus shifting focus from near to distance according to your wish. This is the best possible vision as it utilises all available light for each and every point of focus, however, technology to do this full lens movement does not exist. The best alternative is a lens with fixed optics that allows for some light to do the near work and the rest to do the distance (see image below left).

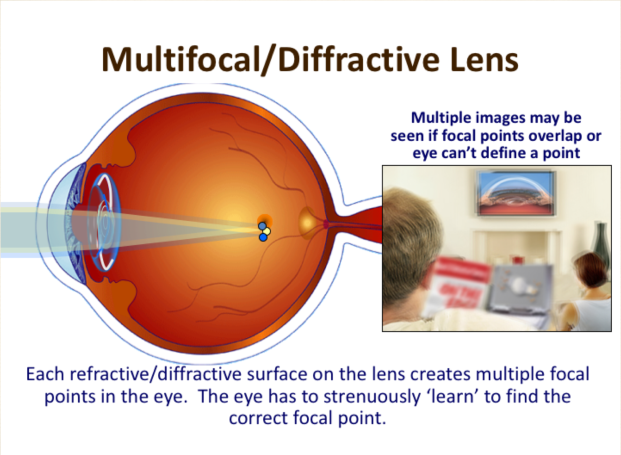

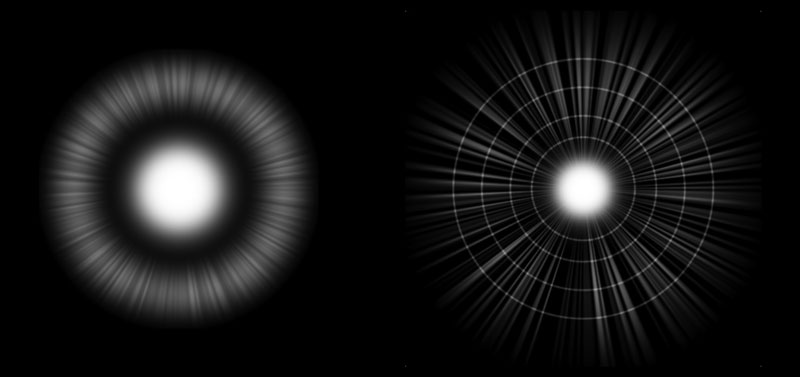

After the surgery, the multifocal lens will be using (depending on lens model) 60-80% of the amount of light for distance vision and the rest 20-40% for near (reading) and intermediate vision (see figure above left). Clearly, the stronger the split of light, the better the near vision and the higher the risk of blurry, foggy vision with glare and haloes of multiple rings. As the split of light creates multiple images and one image is superimposed on another the brain is called upon to do something unusual something for first time, to make both images clear. This requires neuroadaptation, for it is the brain that make sense of our visual world.

The human brain manages to combine disparate images from two eyes in order to achieve a single unified picture, rich with depth perception called stereopsis. Multifocal lenses override the “one eye, one image” construct by allowing for multiple foci, thus producing an image that is variously focused and defocused within a single eye (see figure above, middle). And since the visual cortex has no prewired circuitry with which to digest the information from multifocality, the brain requires a period of adjustment. Neuroadaptation is the process by which the necessary neurocircuitry is put in place to mediate this new type of visual challenge. It means the circuitry that is in place is not sufficient to deal with this new challenge. New circuitry has to be laid down. [Pat Phillips, New Lens, Same Brain: The Importance of Neuroadaptation].

This means that the vision will be a little bit weaker or of a "soft focus", especially if you are in an environment that the light is not bright enough (as is in the evening and at night). Therefore, do not expect to have as good distance or near vision as you currently do with your respective glasses. In other words, when you assess the result of the surgery a day or a week later you would be expected to say: ‘yes, I can see well distance and well near, however, my vision is a bit blurry or not as sharp/crisp as before with my glasses! why?’ The answer is because you’re using only 60% (or 80%) of the light for the distance vision and you are comparing this to before surgery that was 100% and obviously that cannot be the same unless you have had a cataract.

Side effects and complications

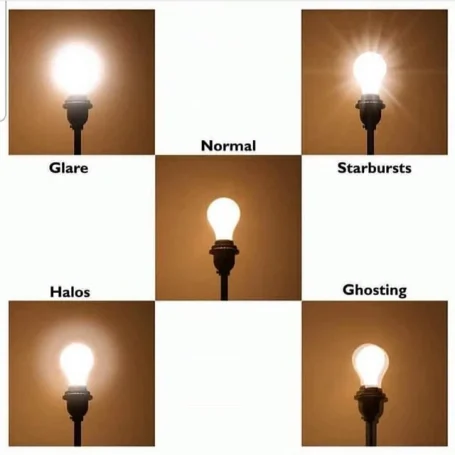

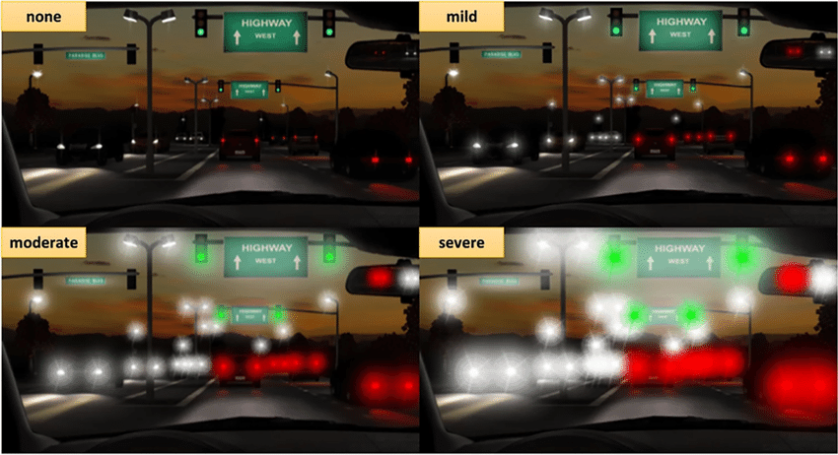

The split of light is the reason why the common side-effects (SE’s) of the surgery occur however, they can be more prevalent in people with dry eyes (OSD), previous laser eye surgery, residual prescription or astigmatism or later on the development of PCO. These are called dysphotopsias and can be a combination of varying degrees of night glare, haloes, starbursts and ghosting or shadowing that happen because when you look in the distance at the headlights of the oncoming traffic or say the subtitles on a movie, the light that passes through the reading part of the lens creates an out-of-focus image (ghost image) that scatters light inside the eye. This is something that the brain should suppress within months but for less than 1% of the patients, this could mean an inability to drive safely at night which, may last for the best part of a year. Other less prominent SE’s could include the presence of a crescent-shaped temporal shadow or edge of the lens effects, small narrowing of the visual field, the perception of seeing through a fish ball, floaters and transient dry eyes.

Overall, when asked a year after the surgery 96% of patients are happy with the outcome of their surgery (that is 85% for plano presbyopes: people that needed glasses only for near vision prior to surgery) and recommend it to their friends and family despite the fact that 10% of them still use some form of glasses and 5% have problems with night driving.

The main complications (all can be helped with additional treatment) are:

- Refractive Surprise: 8% of the patients would require additional laser treatment to correct residual prescription (this would account for more “blurry” than expected vision) this is higher if you had a previous eye surgery (laser or otherwise)

- PCO: 5% per year. An opacification of the capsular bag that surrounds the IOL and decreases vision. It is easily treatable with YAG-Laser, a 20 seconds non-invasive cleaning performed as an outpatient appointment.

- Iritis: 5%. Mild inflammation after cessation of drops. Easily treatable with more steroidal drops.

- CME: 1 in 200. It is a bruising of the back of the eye starting around 2 months after surgery, induces blurred vision for a month but settles spontaneously and can be helped with some drops and tablets.

- PC Tear with/out Vitreous loss: 1 in 2000. A tear in the bag that contains the natural lens and now will support the artificial lens. This may affect the position or choice of lens implantation (esp. in hard cataracts).

- IOL Exchange: 5 in 1000. This non-routine surgery involves the change of a MF IOL to a monofocal IOL due to intolerability of SE’s. Surgery usually takes place 9 -18 months postop and results in restoration of good QoV.

- Retinal Detachment: 1 in 3000. A separation of the retina from the wall of the eye like a wallpaper coming off the wall. It is up to 10 times more common in shortsighted patients and those under the age of 50.

- Infection: 1 in 30.000. This is the most serious complication and may lead to vision loss depending on the type of microbe involved. It is unlikely to happen after the first few weeks after the surgery.

Helpful video from the manufacturer J&J Vision of the Tecnis ZMA IOL

This is one of the early bifocal multifocal IOL models with very good near vision equivalent to +4D strength at 30 cm reading distance. It is associated with a high number of QoV side-effects. The split of light is 60/40 (%) for better near, less distance vision.

Helpful video from the manufacturer J&J Vision of the Tecnis ZXR IOL

This is the first enhanced depth of focus (EDOF) IOL with very good intermediate and distance vision but rather weak near vision equivalent to +1.5D strength at 40 cm reading distance. It is associated with a small number of QoV side-effects. The split of light is 80/20 (%) for less near and better distance vision

Helpful video from the manufacturer J&J Vision of the Tecnis Synergy ZFR IOL

You can consider this lens as a hybrid trifocal IOL. It combines defractive bifocal and EDOF optics resulting in stronger near vision than an EDOF with a better intermediate vision than a bifocal however it has a slightly weaker clarity or QoV characteristics than a bifocal IOL.

Guidance for RLE by the RCOphth

Please read the patient information leaflet on Refractive Lens Exchange by the Royal College of Ophthalmologists opposite, to obtain an independent opinion of the above mentioned risks and side effects of the surgery

© Copyright. All rights reserved.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.